May Day Traditions

When we think of May Day, in a traditional sense, we think of maypoles, ribbons, Jack in the Green and Morris Dancers. In the United Kingdom, celebrations of May Day can be traced back to two sources, the Roman Floralia and the Gaelic Beltane.

Floralia was an ancient Roman plebeian festival in honour of the goddess Flora. It lasted from 28th April to 3rd May and embraced a licentious, pleasure-seeking atmosphere, with gladiator contests, theatrical performances, circus events and dancing.

Beltane was observed throughout Scotland, Ireland and the Isle of Man. It marked the beginning of summer and turning out the cattle to summer pastures. It is a fire festival, incorporating rituals to protect livestock, crops and people and to encourage growth.

Dancing around the maypole is a tradition found across Europe, including England and stretching into parts of Scotland and Wales. The earliest record of a maypole is found in a Welsh poem of the mid-14th century, although they became well-established across southern Britain during the period 1350-1400.

Support, or otherwise, for May Day traditions went in and out of favour through the centuries, according to the prevailing religious influence of the times. In the 16th century, the rise of Protestantism led to increasing disapproval of maypoles and other May Day practices, regarding them as a form of idolatry. During the reign of Edward VI, many maypoles were destroyed. When Edward was succeeded by Mary, who reinstated Catholicism as the state faith, the practice of maypoles was restored. Under later English monarchs, the practice varied, including by location. In Scotland, a stronghold of Presbyterianism, the practice was largely wiped out.

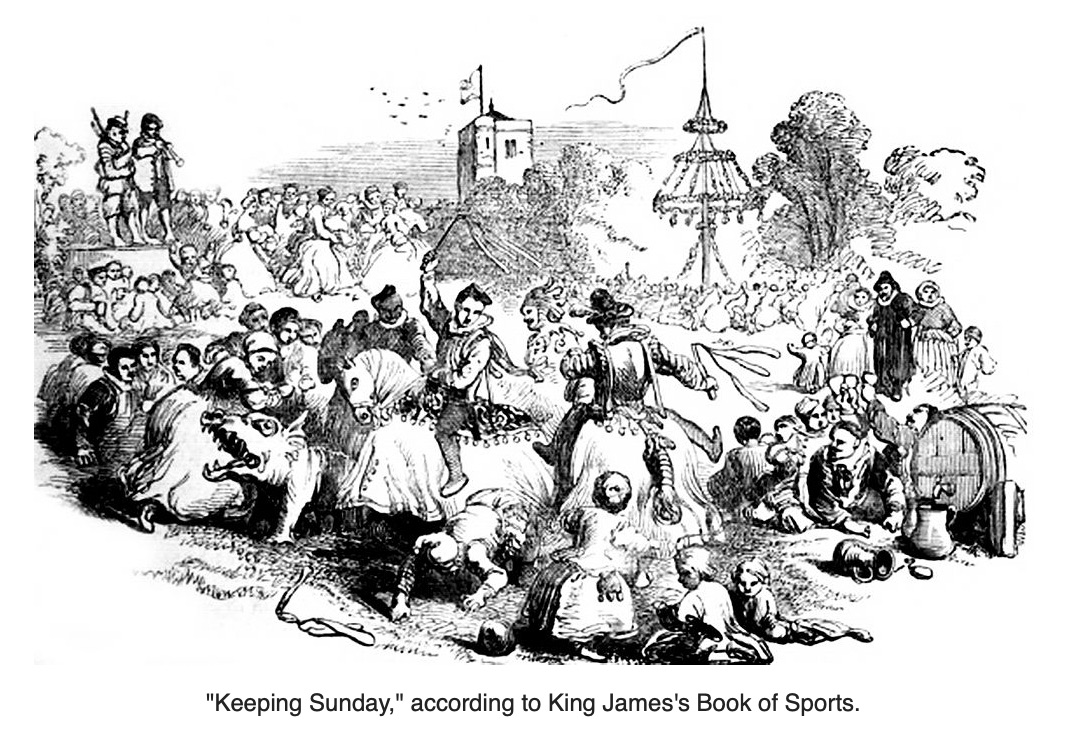

In 1617, King James I, in an attempt to resolve a dispute between Puritans and the gentry of Lancashire, who remained predominantly Roman Catholic, issued a Book of Sports, listing activities that could be indulged in legally on Sundays and Holy Days, so as to limit the killjoy restrictions that the Puritans wished to impose. Archery, dancing, and ‘leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreations’ were deemed to be acceptable. ‘May-games, Whitsun-Ales, Morris dancing and the setting up of May Poles’ were also considered to be harmless. These activities were permitted, with the proviso that they should take place only after evening service and that only those who had attended service (thus excluding Catholics) were eligible. The Book of Sports was designed to weaken the puritan position and to undermine the authority of preachers.

An ordinance of 1644 described maypoles as ‘a heathenish vanity, generally abused to superstition and wickedness’. In the countryside, May dances and maypoles appeared sporadically even during the Interregnum, but the practice was revived substantially after the Restoration, in 1660.

By the 19th century, the maypole had become absorbed into the symbolism of ‘Merry England’. The addition of intertwining ribbons seems to have been influenced by a combination of 19th century theatrical fashion and visionary individuals such as John Ruskin. Yet the maypole continued to be a pagan symbol to some theologians.

Jack in the Green is an English folk custom associated with the celebration of May Day. It involves a pyramidal or conical wicker or wooden framework that is decorated with foliage being worn by a person as part of a procession, often accompanied by musicians.

The Jack in the Green tradition developed in England during the eighteenth century. It emerged from an older May Day tradition – first recorded in the seventeenth century – in which milkmaids carried milk pails decorated with flowers and other objects as part of a procession. Increasingly, the decorated milk pails were replaced with decorated pyramids of objects worn on the head, and by the latter half of the eighteenth century the tradition had been adopted by other professional groups, such as chimney sweeps. The earliest known account of a Jack in the Green came from a description of a London May Day procession in 1770. By the nineteenth century, the Jack in the Green tradition was largely associated with chimney sweeps.

The tradition died out in the early twentieth century. Later in that century, revivalist groups emerged, continuing the practice of Jack in the Green May Day processions in various parts of England.

The suggestion that Jack in the Green represents the survival of a pre-Christian fertility ritual has attracted the interest of folklorists and historians since the early twentieth century. Although this became the accepted interpretation in the mid-twentieth century, it has subsequently been rejected and is now generally acknowledged to be a historical development of the eighteenth century.

The first English record of Morris Dancing was in the mid-15th century. The term is widely believed to derive from Moorish dance; comparable records and terminology are found in several European countries.

Little is known about the folk dances of England prior to the mid-17th century although, as described above, Morris dancing is specifically mentioned in the Book of Sports. Following the Restoration, Morris dancing continued in popularity until the industrial revolution and its accompanying social changes. By the late 19th century, and in the West Country at least, Morris dancing had become more of a local memory than an activity, until the folk song collector, Cecil Sharpe, became a key figure in supporting its revival, from 1900 onwards.

There are many local variations of Morris dancing, including the nature of the dances, costumes and characters associated with the dances.

These May Day traditions, harmless as they seem today, nevertheless hint at their past associations with pagan rituals and an undercurrent of belief that both beckons and hints at mysteries.